Reviews

AN ARTIST DIGS DEEP INTO ROCKY HEART OF MOW

Jack Simcock’s “at home” exhibition – his 30th one-man show – is the culmination of a decade of self-admitted success – success which has been richly merited. The exhibition comprises 56 catalogued oil paintings, and many others, unnumbered, stand around in the familiar way of artist’s studios. On the tables there are drawings and brochures illustrated with some of his finest paintings. The exhibition is staged in his own home, West View, Primitive Street, Mow Cop. It fronts upon two steep hills at right angles one to another, hard by Primitive Chapel. The setting is itself historic, for things happened more than a century ago in Mow Cop which deeply bit into the lives of North Staffordshire people. Although so near to the Potteries, it is still a rather strange world entirely different character from the great industrial region of the Potteries. On the other side of the house the land falls away fairly sharply to the vast expanse of the Cheshire Plain.

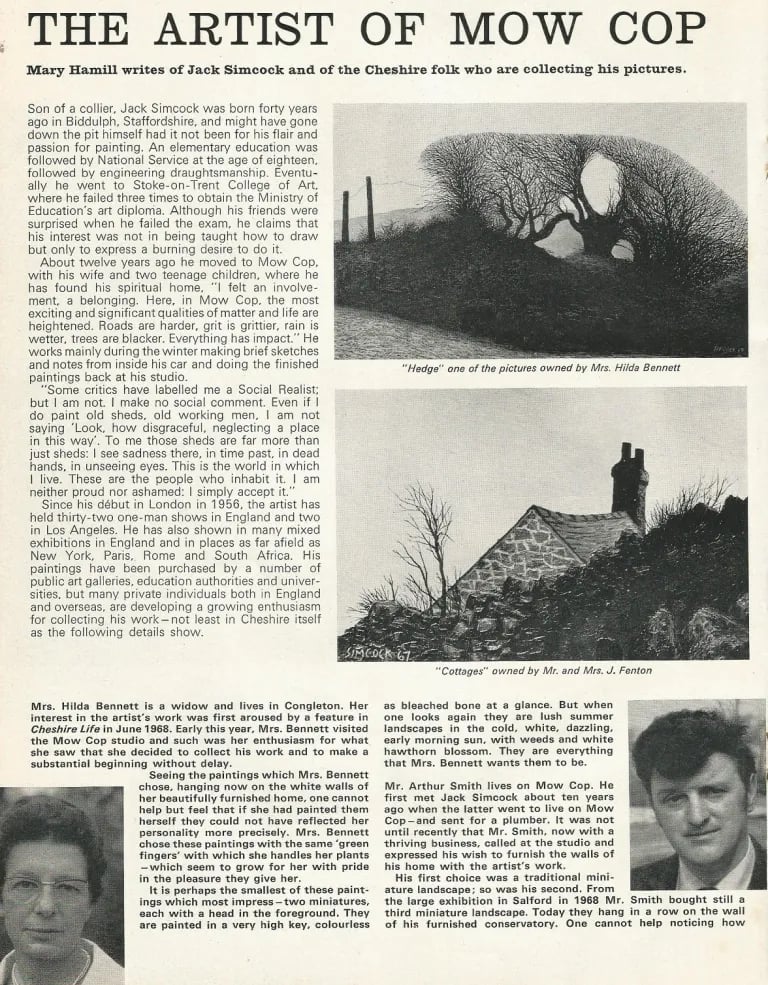

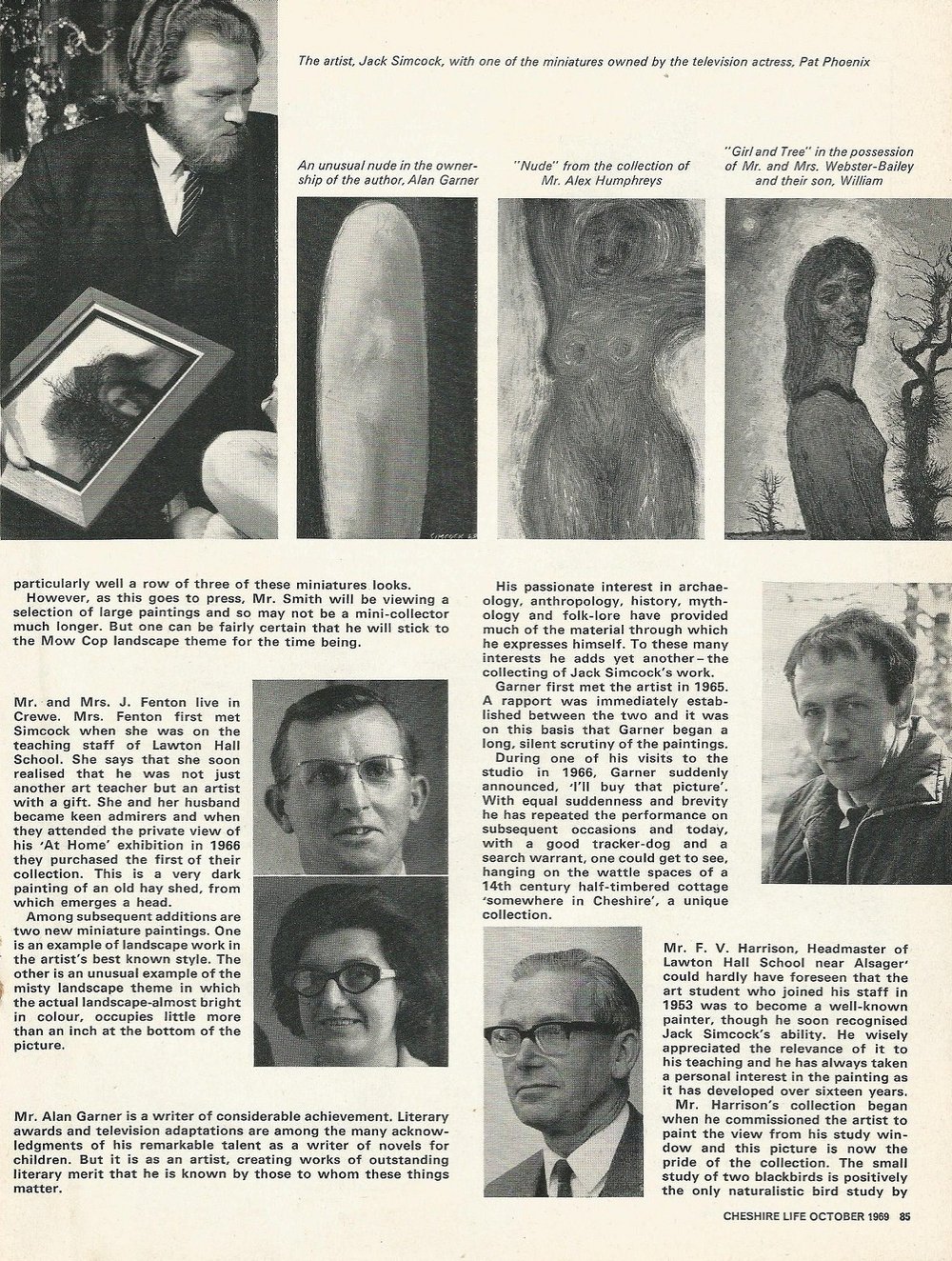

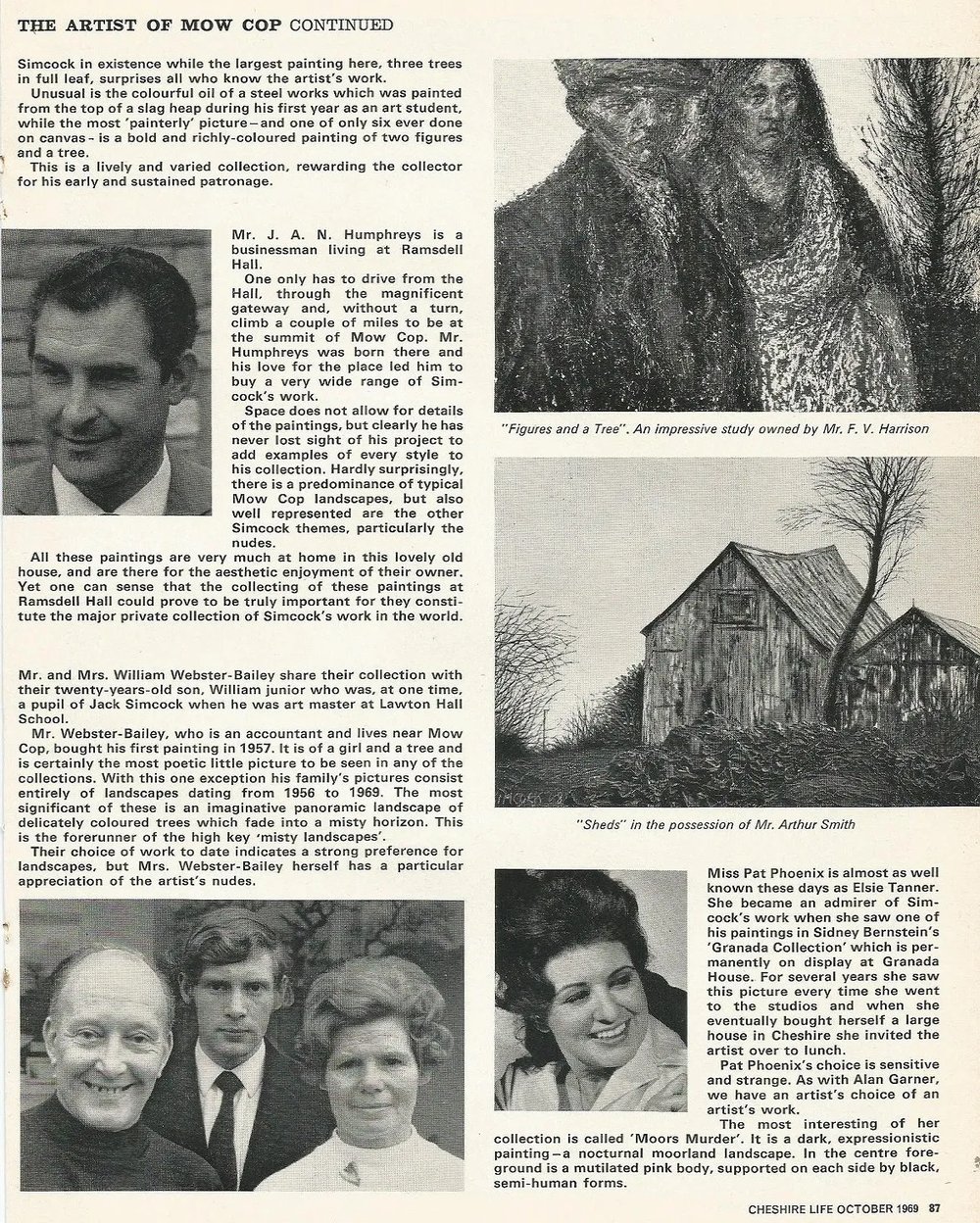

Two rooms of the house are given over to miniature landscapes of Biddulph Moor and Mow Cop, studies of cottages and outbuildings, greenhouses and chicken coops, all recent work. The cellar has been converted into a gallery, and is hung with a series of nudes, “the first full showing” of them in this country. The word nude perhaps needs some qualification because Jack Simcock’s approach to the human body is not by way of anatomical structure and bears little relationship to the nude as understood in history. He appears to have been searching for rhythmic relationships of form suggested by the human body. Some are quite lovely. The studio and garage house the larger pictures, some of which belong to the “artist’s private collection.” This is almost the perfect setting for Jack Simcock’s work, because we are not only in the environment of the artist, we see him in his own home, his wife and children about him, and the “motifs” of his art scattered over hillside and moor. This is his world, and as we examine his pictures, we can relate the man to his work and ponder on the reasons why his painting takes the rather sombre form that it does. There is no doubt that Jack Simcock has quarried deeply into the rocky heart of Biddulph and Mow. He knows this landscape as, using the word in the old Hebrew sense, a man knows a woman. To quote a phrase of the poet Francis Thompson, he has drawn “the bolt of its secrecies” and revealed what he feels about its substance and its significance. The evening I visited Mow Cop, all the world was there. Cars lined its steep narrow streets and police regulated the traffic. It was a warm summer night, and the great plain stretching away to the Mersey was swathed in haze and above the meadows rose the lark – a scene to enchant a painter. But there is another and darker kind of magic which these gaunt rocks and this primitive landscape work upon the minds and characters of men and women, and it is this which Jack Simcock has set out to capture. The perpetual challenge of nature to man is here. There are one or two pictures in this exhibition in which a sense of infinite space has held the artist’s imagination, but generally Jack Simcock has focussed his vision sharply upon the near rather than the far, upon the rocks and stones shaped by man into habitation and home, the features in other words which give to this unique landscape its peculiar personality.

There is no need to select from this collection of pictures works for special mention, except to indicate the variety and (not immediately apparent) the richness of colour of some of them: “Scarecrow in the snow” for example, is a white picture (not a dark one), “Two Women” is another richly coloured painting, and then there are the panoramic views, the fine portrait head, the paintings of buildings and cattle and the nudes. This splendid collection of paintings and drawings by one of the leading artists of his generation is being held simultaneously with a one-man show of 30 pictures at the Piccadilly Gallery, London – testimony not only to the creative genius of the artist, but also to his single minded devotion to his chosen vocation. Both exhibitions remain open until the end of July.

R.G. Haggar Evening Sentinel July 8th 1966

ART ON PRIMITIVE STREET

Primitive Street is the mantelpiece of Mow Cop. On the top shelf of a great fireplace of a Potteries village which is embossed on a hill 1,000 feet high. There are fields, red houses, pit heaps and trees, one of them just an arthritic stump. In the view that Jack Simcock, philosopher-painter, sees from his house in Primitive Street. He is unlikely ever to paint the fields: when he paints the houses they will probably appear black, scarcely lighter in tone than the pit heaps: and he will never paint the stumpy tree when the sun is on it. There is no sunshine in any of his pictures; no leaves on his trees: he paints only between late September and March.

Simcock, at 31, has been painting for five years, averaging about fifty pictures a year and selling most of them. He has had nine exhibitions to himself, four of them in London and one in Los Angeles, and now has one opening in New York and another in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Yet he says: “I can’t talk about myself as a professional. When people talk about painters I don’t identify myself with the group they are talking about. Painting is a way of life for me: a philosophy.”

He has never used any subject outside the Potteries, and mostly he paints from subjects found within a mile of his home: terraced –row landscapes, for example in blacks and greys, sometimes under a blotched white sky and with a face or a full figure as a merged foreground. The landscapes are actual and are sketched beforehand: the faces and figures are imaginary “worked into the picture because at a certain stage they seem psychologically right: as much a part of the landscape as a house or a telegraph pole.” He is the only son of a miner, born into a village of terraced brick houses: dark little homes with lace curtains. He was brought up by “tired people in a tired, tasteless world of work and worry,” and he hated it from an early age. “I wanted to go away to London or abroad, anywhere, just to get away.” But now he lives in his tall grey house with his wife and two children, two miles from where he was born, and says that he never wants to leave. He thinks on paper, writing “art notes,” and “philosophic notes” with a vague (and unrealised) view to publication, but much more for his own clarification. The language is in glaring contrast to the dramatic and uncluttered nature of his painting. In an article (published in “Art News and Review”) explaining how he began painting, he wrote that “an overwhelming awareness of the disturbing reality of my environment and a growing sympathy and involvement with it” developed in him “a compulsion to absorb it into a form which I could more readily perceive.”

So he paints only what he knows and understands. “I could never paint the sea.” But he does not regard himself as a regional artist. He is not painting Mow Cop, although his neighbours will tell you he is, because they recognise his scenes. His paintings, to quote again from his “Art News and Review” article, “express my concept of all visible matter.” He says he makes no attempt to communicate to other people in his work. “I ask my own questions in my painting and answer them. If the solution is right to me that is all that matters. If other people like my work and buy it, I am pleased, because I want a comfortable house furnished the way I want it: but the reason why people buy my work is not important to me.”

He spent four years at a local school of art, but in the last two years he ignored most of the classes and sat on pit heaps painting by himself. He failed in three attempts to get an art teacher’s diploma, but found a school where he still teaches three days a week. He says that he has never been conscious of adopting a style. “I’ve never found the technicalities of painting difficult or very interesting.” He paints quickly, using a knife, and seldom takes as long as eight hours to complete a work. Yet one gallery where he has exhibited praises particularly his “beautiful technique” while regretting that with his unchanging blacks and greys he has “found himself a formula which is a bit of a straightjacket.”

Simcock would reply to this that he does not understand what is meant by “his formula,” and that the criticism “has no significance” for him. He paints what is significant: and grey stones are and roses and sunlit red bricks are not.

(Review from “The Guardian” written by Arthur Hopcraft, 1961)