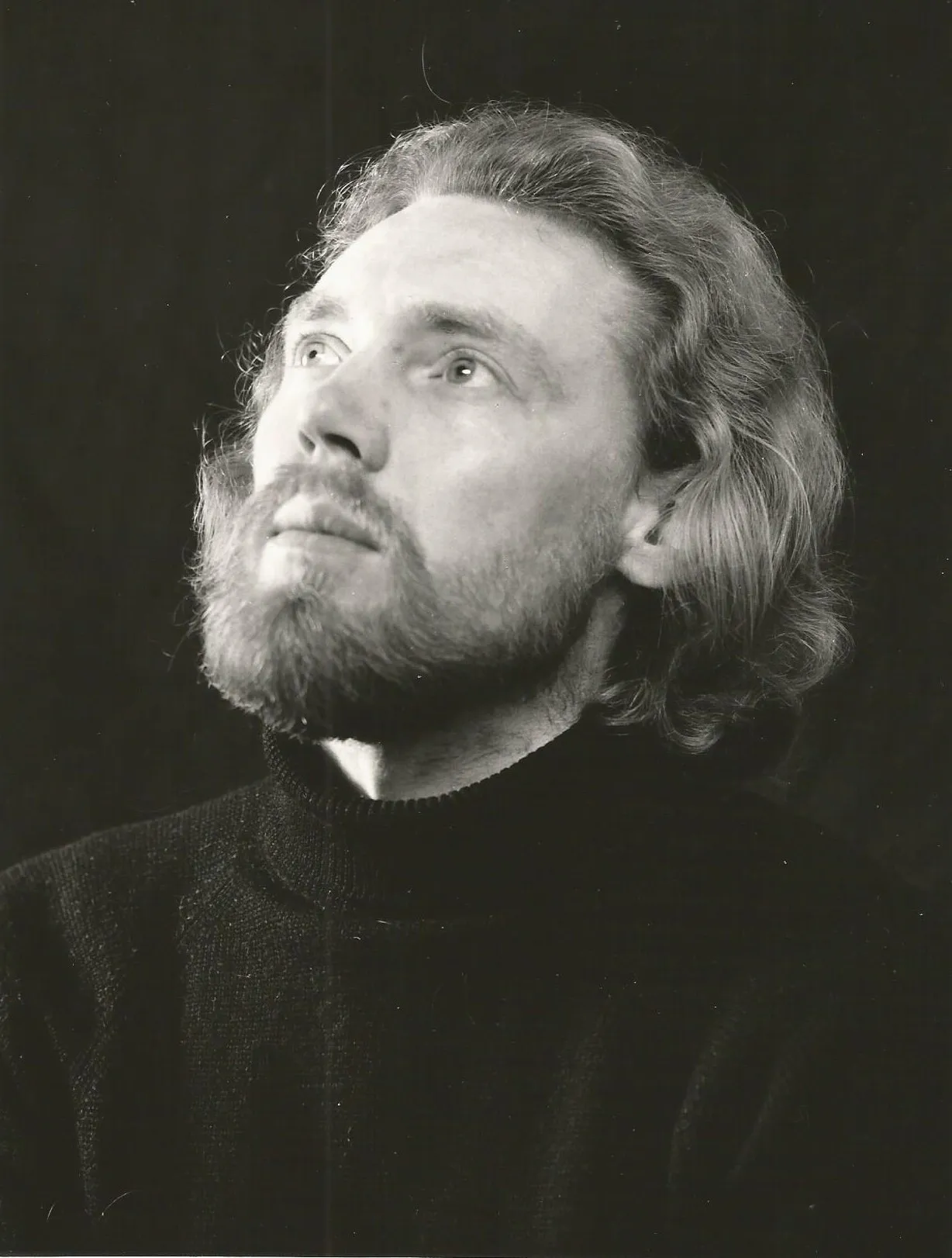

Jack Simcock

Painter & Poet

Biography

Jack Simcock was born on 6th June 1929 in Biddulph, Staffordshire. The son (and only child) of George (a coal miner) and Lily Simcock.

From the ages of 13 to 15 he attended the Junior Technical School in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent. His first job was in the drawing office of a company which designed and manufactured coalmining machinery. He also went to evening classes at the Wedgwood Institute, Burslem, to study building construction and science for the City and Guilds.

In 1947 he was Conscripted into the army, where he served for 2 years. It was here that he started painting, mostly in watercolours, and selling them for pocket money to friends and family. At the time he signed his work “Smickco”. Demobbed in 1949, he concluded that painting was his passion and started at Burslem Art School later that same year. This was when he began to paint in oils, and go out sketching locally.

It was also in 1949 that he met Beryl Shallcross, whom he married in 1952. During his time at Burslem Art School he failed his National Diploma in Design a total of 3 times.

In 1953 he was employed as the Arts and Crafts Master at Lawton Hall Private School in Cheshire, where he taught until 1967.

Jack and Beryl had 2 children. Tony born in 1954 and Janis born in 1956. The family moved into “West View” at Mow Cop in 1958, where he lived until his death in 2012.

It was in 1956 that he got his big break, when his paintings were snapped up by Godfrey Pilkington at the Piccadilly Gallery, Cork Street, London, when he took them around the London galleries.

He had over 50 one man exhibitions from 1956 until 1981. His paintings were bought by a wide range of collectors, including the rich and famous, and are represented in a number of public galleries including the Tate Gallery. In 1975 he published his autobiography “Simcock Mow Cop” along with a book of poems “Midnight Till Three”. He was always an obsessive writer along with his painting.

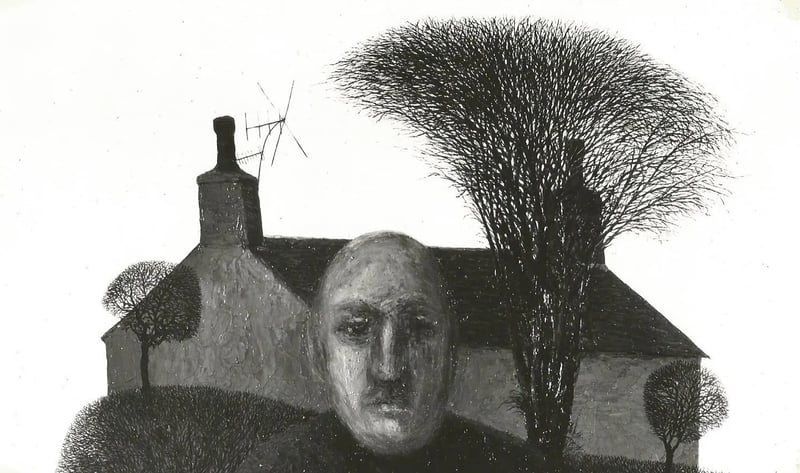

Jack’s painting style was easily recognised for it’s dark, gloomy look. Landscapes, cottages, trees and faces all within a light sky. In early 1980 he changed his style of painting, needing to include more colour and express himself in different ways, a natural progression for any artist. This resulted in him being dropped by the Piccadilly Gallery, and most of his collectors.

The coloured paintings have been shown in one man exhibitions at The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery early in 2001, and the Moorland Arts & Antique Centre, Leek, Staffordshire later in 2001, and at Keele University in 2012 in a 3 man exhibition with Arthur Berry and Enos Lovatt. Ironically Jack died the day before the opening.

The last painting was completed in 2011, but Jack was drawing and writing right up to a few days before his death on 13th May 2012. He was in heart failure and suffering from bowel cancer.

Obituary

The artist Jack Simcock died on Sunday 13 May 2012, at the age of 82, on the eve of the opening of an exhibition of previously unseen work in uncharacteristically colourful abstract style.

He had always done abstracts, some of which were stylised versions of his more typical ‘landscape and head’ theme. And some of them, and his heads and nudes, were colourful. But Simcock was and will remain best known for dark moorland landscapes and villages, with buildings that seem to grow out of the earth, and often a foreground figure or head. Or is it a boulder? They are realistic, yet as exaggerated in their sombre grittiness as Wuthering Heights.

The trees are always bare and the roofs are always wet. He actually waited for the combination of rain and a certain kind of light to make the roofs shiny before he would venture out sketching. The resulting gloomy landcapes under light skies give a monochrome effect, but Simcock hated people referring to them as black and white. There was much subtle use of dark browns and dark reds and dark blues and dark greens. He painted in oils on hardboard, mainly using a palette knife, which itself imparted a characteristic rugged texture.

The typical Simcock painting was often thought to merge his coal mining origins and the adjacent moorland landscape, a combination of environment that is so typical of much of northern England (or the Welsh valleys). He was in fact born in a coal mining valley, at Biddulph in North Staffordshire, just north of the Potteries, in 1929. His parents both hailed from Biddulph Moor, once famous for the surly individuality of its inhabitants. Father and grandfather were coal miners, who nevertheless retained a strong sense of their roots among moorland farmers and stone masons. The grandfather was killed at Chatterley Whitfield Colliery when Simcock was 12.

So the presumption of the two strands coming together in these paintings has some foundation. The Simcocks were also Primitive Methodists, the working-class sect that had more in common with old-time Quakerism. Both Puritan and Primitive are words that have to enter any discussion of Jack Simcock’s work.

He was by no means a primitive painter, it was rather his subject-matter that was primitive. He could not escape the word anyway, as from 1958 to his death he lived on Primitive Street, Mow Cop, adjacent to the spot where Primitive Methodism began in the 1800s. It was only a matter of time, as his career took off, before a newspaper headed a review of one of his exhibitions ‘Art on Primitive Street’.

Puritanical however Simcock certainly was, in his painting and in his personality. A convinced atheist, he lived it and advocated it with a grim commitment worthy of the most Quakerish of his ancestors. He liked to engage in religious debate, but debating with him was pointless. He considered himself a great ‘conversationalist’, but his partners in these marathons needed to be very good listeners. He was an armchair expert on many things, including medicine, music, philosophy, and roofing; and his egotism filled in where his knowledge fell short.

At the time when everyone was talking about the ‘three tenors’ and selecting their favourite, he held forth at length on the superiority of Carreras. When the person with whom he was having this conversation thought it was his turn and began to say his own favourite was Pavarotti, he was stopped with a dismissive hand gesture, as Simcock leant forward and said emphatically ‘Ah, but that’s just your opinion’.

He was active until very shortly before his death, which was from heart failure related to cancer of the bowel. But he had always enjoyed illness, and had been predicting his imminent demise from at least his thirties. The Reader’s Digest medical encyclopaedia was always by his chair. More than once he had to change doctors because his self-diagnosis conflicted with their opinions.

He had been diagnosed at quite an early age with what used to be called ‘nerves’, and was consequently a lifelong addict of the pills that it was once fashionable to prescribe for that imaginary ailment. It was hard to tell whether it was he or the pills that were manic depressives. Much that was selfish and irascible in his personality might possibly be laid at that door, co-existing as it did with humour, compassion, and his almost mystical attachment to the landscape that inspired his art.

These deeper emotions expressed themselves in his ceaseless creativity. The creative urge in him was so great that having painted in his studio for many hours his relaxation would consist of writing (usually during the night – his book of poems is entitled Midnight till Three) or composing music, or occasional forays into sculpture. Little came of these other activities, except for the poems and an autobiographical work, entitled Simcock Mow Cop (the words he used in answering the telephone), both published in 1975.

His father never wanted him to be a coal miner. He studied at Burslem Technical School, where his aptitude for technical drawing led to work in an architect’s office. Conscripted into the army and posted to the Royal Army Medical Corps, he graduated from the ‘shit squad’ to the task of painting instructional posters on hygiene (he loathed flies for the rest of his life). More importantly he started painting seriously, and decided he wanted to go to art school.

He returned to Civvy Street in 1949 as ‘Smickco’, an aspiring commercial artist. His father helped him through Burslem Art School, an excellent training ground in fine and decorative arts, being at the heart of the ceramic industry. Later for a brief period he taught there. The first painting he exhibited was purchased for the City of Stoke-on-Trent Art Gallery for £3.

He admired or anyway was influenced by Van Gogh (giving Vincent as a middle name to his son), Munch (Simcock’s heads do not scream, but they are the unmistakeable offsprings of Munch’s), and Bonnard, who remained his favourite non-contemporary painter. His mentor at Art School and for a time after was Arthur Berry, a greatly under-rated North Staffordshire painter.

In 1953 he was astonished to learn that he had failed the diploma examination in painting. He took it twice more and failed it twice more. In spite of which, both his sense of ‘emergence’ as an artist and his seemingly charmed life flourished during the 50s, in tandem with marriage, having children, and making a home of his own. His father gave him a house. He got more or less the first job he applied for, as art master at Lawton Hall School, a private school not far away in Cheshire.

And when he set off to London in 1956 to perform the hopeless task of dragging six paintings round the off-Bond Street private dealers’ galleries, the first gallery he walked into brought him face to face with Godfrey Pilkington, an astute gallery owner and genial spotter of new talent. Annual one-man shows at the Piccadilly Gallery and various provincial venues, well reviewed and often selling-out, with occasional sales to celebrities, established a reputation which was at its height during the 1960s and 70s.

His career total was over fifty solo exhibitions. Highlights included an open-house exhibition at his home on Mow Cop in 1966, a major exhibition (his largest ever) at Salford City Art Gallery in 1968, and an exhibition combining paintings and photographs at the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, in 1979. The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery held a retrospective in 2001. Works were acquired for a number of public collections, including the Tate Gallery and a scatter of municipal art galleries in the midlands and north.

After giving up teaching in 1967 his boast (whether correct or not) was that he was the only contemporary British artist able to support a wife and young children exclusively on the income from selling his paintings. One of the things that made it work was his knack of persuading local tradesmen (plumbers, builders, hi-fi dealers, even a hairdresser) to accept paintings in lieu of payment. But the most surprising thing about it was that he had long since turned his back on anything commercial, and usually refused commissions: he was an ‘artist’ and he painted only ‘Simcocks’.

In the 1980s he changed his style – not for the first time, though the pale ‘misty’ landscapes had proved popular and seemed a natural progression. But the new, more shockingly colourful paintings, which were in fact an evolution from the misty landscapes, and later from the stylised heads, alienated his long-suffering dealer as well as his established collectors. He continued painting but only rarely exhibited. He also did more writing and drawing.

In spite of considering himself a ‘working-class lad’ and in spite of being a good art teacher, he had a haughtily purist notion of ‘art’ and held recreational painting in disdain. Though in fact he disliked most fellow artists too, particularly those with whom he found himself compared – such as Lowry. He had little truck with the social side of the art world, and was reluctant even to attend his own private views. On and off he was a semi-recluse; while being cantankerous and egotistical made it difficult to sustain friendships.

The one spurned friend he regretted and the fellow painter he most admired was Arthur Berry (who died in 1994). Their philosophy was the same: they thought sheds on an allotment or a dry stone wall were deeply moving expressions of the predicament and spirit of working-class human beings in a godless universe.

He was pleased in his last days to be involved, with the encouragement of his daughter and two granddaughters, in arrangements for an exhibition at Keele University where (unthinkable to him at one time) he shared the stage with Arthur Berry and a living painter with whom he had also been good friends, Enos Lovatt. It was an opportunity to show the colourful abstracts of his last ‘period’, which he doggedly persisted in painting and in believing were the true development of his otherwise inexpressible creative passions and artistic integrity. He died the day before the exhibition opened.

Jack Simcock (he was actually christened Jack) was born in Biddulph, Staffordshire, on 6 June 1929, and died at his home at Mow Cop, Cheshire, on 13 May 2012. In 1952 he married Beryl Shallcross, who died in 1997. They had a son and a daughter.

TS 2012

About Us

We are Jack Simcock’s daughter and granddaughters. Janis, Kate and Deborah Beats.

Janis

I am now based in South Manchester, where I moved after living for a year at my dad’s house, “West View” at Mow Cop, Cheshire. I was unable to permanently live at “West View” as it needed major works and upkeep, and I had always been a little afraid after my dad’s many ghost stories!

I’ve become a volunteer for the RSPCA, mainly fostering cats and kittens. My obsession is gardening, and I spend most days digging and trying to grow veg, and hopefully eat it before the snails, greenfly, caterpillars, birds etc.

Kate

I have been working as a Teaching Fellow at the University of Warwick since 2012, in the Department of Classics and Ancient History. Since beginning my studies in 2002 at Warwick, my research has taken me to libraries across the UK and Europe, to archaeological sites in Greece and to museum stores in Cardiff and Coventry. I obtained my doctorate in 2012. My particular interest is ceramics, and the older and dustier the better. You know what they say, you can take the girl out of the Potteries, but you can’t take the Potteries out of the girl.

Deborah

I live in South Manchester, which is why my mum moved here after my grandad’s death. We enjoy going back to Mow Cop to reminisce about him and looking at the scenery that influenced his traditional paintings.

Reason for website, and why now?

I (Janis) cared for my dad for nearly 5 years prior to his death. We became very close and had many conversations, during our daily time together, about how I should deal with his work after his death (death was his favourite subject, he looked forward to it immensely). We experimented with the internet (he’d always said he’d never use any of these modern gadgets) and we decided to put a few catalogues and drawings on eBay. He kept a little book, with photos of all the drawings we put on, and he wanted daily reports of how many viewings and watchers there were. He couldn’t wait for the auction to end and was very excited when we sold anything. This always surprised me, as he’d refused a number of painting sales for many years, but it wasn’t anything to do with the money, he just found it entertaining.

This is why I decided to set up a Simcock website, as I know he would approve of showing his work in this way. On here you’ll have access to paintings and drawings never before seen, from early work in the 50’s through to the latest in 2011 just prior to his death, and the opportunity to purchase works which have never been offered for sale previously, among other things. My dad would have loved to have been involved, which of course he is, as without him I wouldn’t have anything to show you! The reason for the timing is as a memorial for the 2nd anniversary of his death (13th May 2012).